Chapter 19: Finale

After Mom got back from the coast, she continued to sketch. On August 10, she sketched her youngest granddaughter, Jenae (22a):

On August 14, after John left for the East Coast, I took her to Clackamette Park and parked on the bank of the Willamette. We watched a kayaker paddling by and landing. She started sketching the scene, all focused concentration for half an hour, a professional at work. While she sketched, I photographed her (22b):

I scanned the sketch when we got home (22c):

She had made the kayak a two-seater, and added some another boat that was going in and out of view at the mouth of the Clackamas. It was unusually complex, too "busy," I thought at first. But what makes the sketch work, I realized much later, is a kind of double shadow of a person projected upon the foliage and the ripples in the right center. She put in an observer, perhaps two, watching serenely, larger, as shadows will be, than the people in the scene.

That night she told my sister Cathy she was dying. Cathy called me. We didn’t know what to think. The nurses were observing her every day!

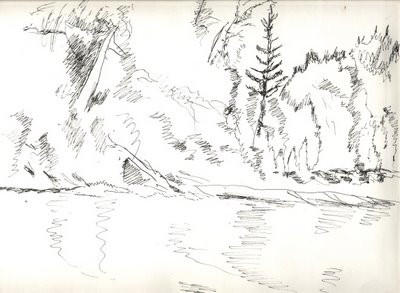

On Thursday her caregiver took her to the Molalla River. There she was able to simplify and abstract so as to bring out the divine beauty of the river (22d). Today there are no people in the scene:

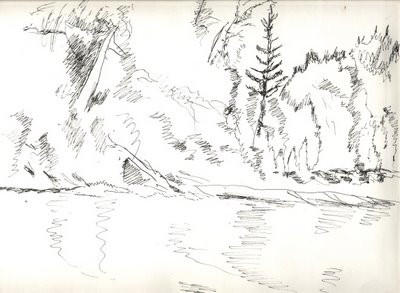

She did one more sketch that was even better, which she called “The Wild Molalla” (22e):

She didn’t say anything about dying that evening, and she seemed ok. But after the next weekend she started feeling very weak. Breathing was more and more difficult. She went to the hospital and had to be put on an artificial breathing apparatus. By the next week she had a confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer that had mastacized to the lungs. It was too late for any treatment.

We called family and friends so that they could say good-bye. On the Saturday of Labor Day Weekend, grandson Wes and his wife Erin brought their small children over, and she played with them with her eyes and hands. On the Sunday, some of the artists from the “pleine aire” group—Leland, Akiko, Eileen, and Sandee—came over to pay their respects. She beamed with recognition. They wrote “We love you” on a piece of paper, and with grandson Brandy holding the paper on a board for her, she wrote back, in a barely legible hand, “I love you too. See you later.” They stayed a while, not just with her but with us. There in the ICU it was like a party, like being at your own wake. I realized that she was dancing with her friends, just like in her drawings of the pines. She was dancing with her eyes and her mouth. Later, when I was alone with her, I found myself dancing for her to the Mozart on her boombox. She watched every move. She couldn’t draw anymore; in fact, she barely acknowledged any artwork of hers we brought in. But she could still dance.

After that long Labor Day weekend, she seemed more and more to be listening to something somewhere other than that hospital room. Occasionally she would open her eyes and give whoever was there a big smile. When that happened, we loved it; it was like a wave that we’ve been waiting for hitting the shore. But then she’d close her eyes again, and it was a long time til the next wave. I don’t think she was unconscious. She was just focused on somewhere else, like in her drawings of the ocean, going off to the horizon. On Thursday when they took her off life support she was still conscious, in her way of occasional flashes of acknowledgement. I think she was ready for what came next, and at peace.

On August 14, after John left for the East Coast, I took her to Clackamette Park and parked on the bank of the Willamette. We watched a kayaker paddling by and landing. She started sketching the scene, all focused concentration for half an hour, a professional at work. While she sketched, I photographed her (22b):

I scanned the sketch when we got home (22c):

She had made the kayak a two-seater, and added some another boat that was going in and out of view at the mouth of the Clackamas. It was unusually complex, too "busy," I thought at first. But what makes the sketch work, I realized much later, is a kind of double shadow of a person projected upon the foliage and the ripples in the right center. She put in an observer, perhaps two, watching serenely, larger, as shadows will be, than the people in the scene.

That night she told my sister Cathy she was dying. Cathy called me. We didn’t know what to think. The nurses were observing her every day!

On Thursday her caregiver took her to the Molalla River. There she was able to simplify and abstract so as to bring out the divine beauty of the river (22d). Today there are no people in the scene:

She did one more sketch that was even better, which she called “The Wild Molalla” (22e):

She didn’t say anything about dying that evening, and she seemed ok. But after the next weekend she started feeling very weak. Breathing was more and more difficult. She went to the hospital and had to be put on an artificial breathing apparatus. By the next week she had a confirmed diagnosis of breast cancer that had mastacized to the lungs. It was too late for any treatment.

We called family and friends so that they could say good-bye. On the Saturday of Labor Day Weekend, grandson Wes and his wife Erin brought their small children over, and she played with them with her eyes and hands. On the Sunday, some of the artists from the “pleine aire” group—Leland, Akiko, Eileen, and Sandee—came over to pay their respects. She beamed with recognition. They wrote “We love you” on a piece of paper, and with grandson Brandy holding the paper on a board for her, she wrote back, in a barely legible hand, “I love you too. See you later.” They stayed a while, not just with her but with us. There in the ICU it was like a party, like being at your own wake. I realized that she was dancing with her friends, just like in her drawings of the pines. She was dancing with her eyes and her mouth. Later, when I was alone with her, I found myself dancing for her to the Mozart on her boombox. She watched every move. She couldn’t draw anymore; in fact, she barely acknowledged any artwork of hers we brought in. But she could still dance.

After that long Labor Day weekend, she seemed more and more to be listening to something somewhere other than that hospital room. Occasionally she would open her eyes and give whoever was there a big smile. When that happened, we loved it; it was like a wave that we’ve been waiting for hitting the shore. But then she’d close her eyes again, and it was a long time til the next wave. I don’t think she was unconscious. She was just focused on somewhere else, like in her drawings of the ocean, going off to the horizon. On Thursday when they took her off life support she was still conscious, in her way of occasional flashes of acknowledgement. I think she was ready for what came next, and at peace.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home